The hyperinflation of content

Most people have no interest in reading AI writing, so why is so much content online now written by AI? The underlying dynamics driving the proliferation of AI writing online, and where we are going.

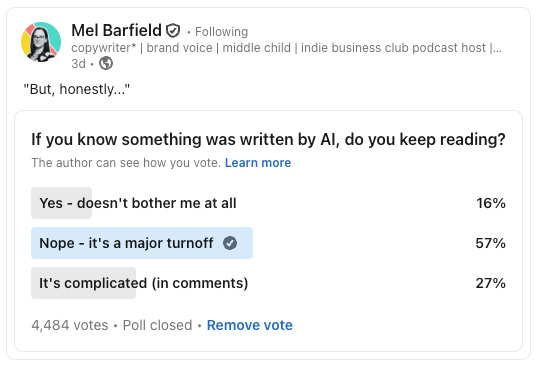

A recent poll of 4,484 people found that 57% stop reading once they know the content was written by AI. The results:

When people know writing is of AI provenance or when they feel like they’re being spammed, they opt out of that content.

For Un•AI•ify users, this poll result is probably obvious because you’re a pro at noticing AI rhetoric. You look for the overuse of words like “essential” and you tune out at the first variation of “It’s not X. It’s Y.”

For most, there’s little attention to give any writing at all, so most content, regardless of how it was created, languishes in obscurity.

With content summarily dismissed for being AI-written, why is AI writing so widely used and tolerated? And what is to come of the Internet as AI-written becomes the default?

The AI-written emperor has no clothes … so why isn’t anyone saying so?

Regardless of the shortcomings of “AI detectors,” like the robust Pangram (or the simplistic Un•AI•ify), the existence of detection tools points to a growing distrust. People are becoming skeptical regarding the provenance of any given piece of content online.

Like the abductive approach of the duck test, “If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck,” the parlance of AI is hard to miss. So while an em dash (—) may mean AI or a professional writer, it might mean nothing. But seen with the ubiquitous “It’s not X — It’s Y,” suspicions of AI become impossible to ignore.

People see the emperor’s new clothes are fake, and most stop reading further (as many as 6 in 10 if the poll is to be believed). However, and this is based on a lot of observation, almost no one says much of anything to call out the swindle.

Why?

For starters, there’s little upside to shouting out “AI!” Instead, the easiest and lowest risk response to noticing that, “This looks like AI writing,” is to close out the content or scroll on.

By disengaging, at least on social media, the poster of the offending “AI slop” may notice their engagement drops. They lack clear feedback, though. They are as likely to assume their content, this time, simply failed to resonate. Or maybe they chalk it up to bad luck. They’ll try again and again. After all, they have nothing to lose.

On the other hand, any engagement invites repeat behavior. As popularized by Daniel Kahneman, people pay attention to what they see. What’s measured. “What you see is all there is.” In the case of the spamming social media poster, they focus on the impressions, engagements, and replies. They think, “Something is working here. Look at these results!” They ignore the dog that doesn’t bark, which is that the majority ignored their content completely. The word slop continues.

All the while, their intended audience has little time and less attention to offer. They have a shelf of books they keep planning to read; an endless stream of entertaining content a thumb swipe away; and the last thing they want to do is focused reading online.

There’s too much content and not enough attention.

How the content engine works

Digital content is cheaply created and cheaply published. This has been the case for years now. Whereas once you had to have a server to publish anything, now you need any one of dozens of social media accounts. Whereas once you had to jump through hoops to do the work of writing, build up an audience over time through engaging content and building relationships with likeminded folks online, now you can create a new account on TikTok in minutes and have new audiences find your content … should you be so lucky.

Every LLM service, whether ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Grok, Jasper, whatever, offers “creators” content whenever they want it. The cost to create, if any, is the creator’s time to prompt and publish. With the right prompt gets you a thousand word blog post in seconds. (Or an image, presentation, video asset, you name it.)

The costs to create content have never been lower, and the supply of content, whether it’s published or not, can grow faster than ever before.

For those who want to create and publish content to win attention, persuade, and profit, using AI to prompt content into existence becomes a “free option,” meaning new content creations offer upside, even if small, and limited downside.

Common content distribution channels like Google search, [fill in the blank] social media, Reddit rely on freely submitted content for their businesses to function, and they depend upon attention-giving users to curate what’s worth consuming. The system, with a lot of help from algorithms that match relevant content to willing audiences, keeps users engaged. And all the platforms monetize against user attention however they can.

All of this happens against a limited supply of attention. So while creators chase every bit of attention they can get, the pie of attention is constrained. Even with AI-supported summaries and other tech-powered filtering, attention cannot hope to grow as fast as the supply of content.

Even though the upside of content creation diminishes, creators lack constraints preventing them from pushing harder and harder. Instead, they can use AI to get more leverage on content creation to do more, to spam harder. There must be a point at which the “juice ain’t worth the squeeze,” but it’s unclear where that point is.

So for now, we get more and more content. While spam was in years past associated with bad actors, now millions (if not hundreds of millions globally) spam each other. They do it at work (via AI-written emails, briefs, memos, whatever), and they do it at play (“Did you see this [sensational content with tenuous if any ties to reality]?”).

Too much content supply = runaway inflation

We are overrun with content that grows faster than our ability to make sense or identify what’s actually worthwhile. Like a DDoS attack that overwhelms a server’s ability to handle incoming requests, the deluge of content overwhelms our ability to filter signal from noise.

What will stop this process from continuing until so much of the content market is saturated that the benefit of paying attention to any of it is lost? This has all the markings of a runaway process, a runaway inflation of content online.

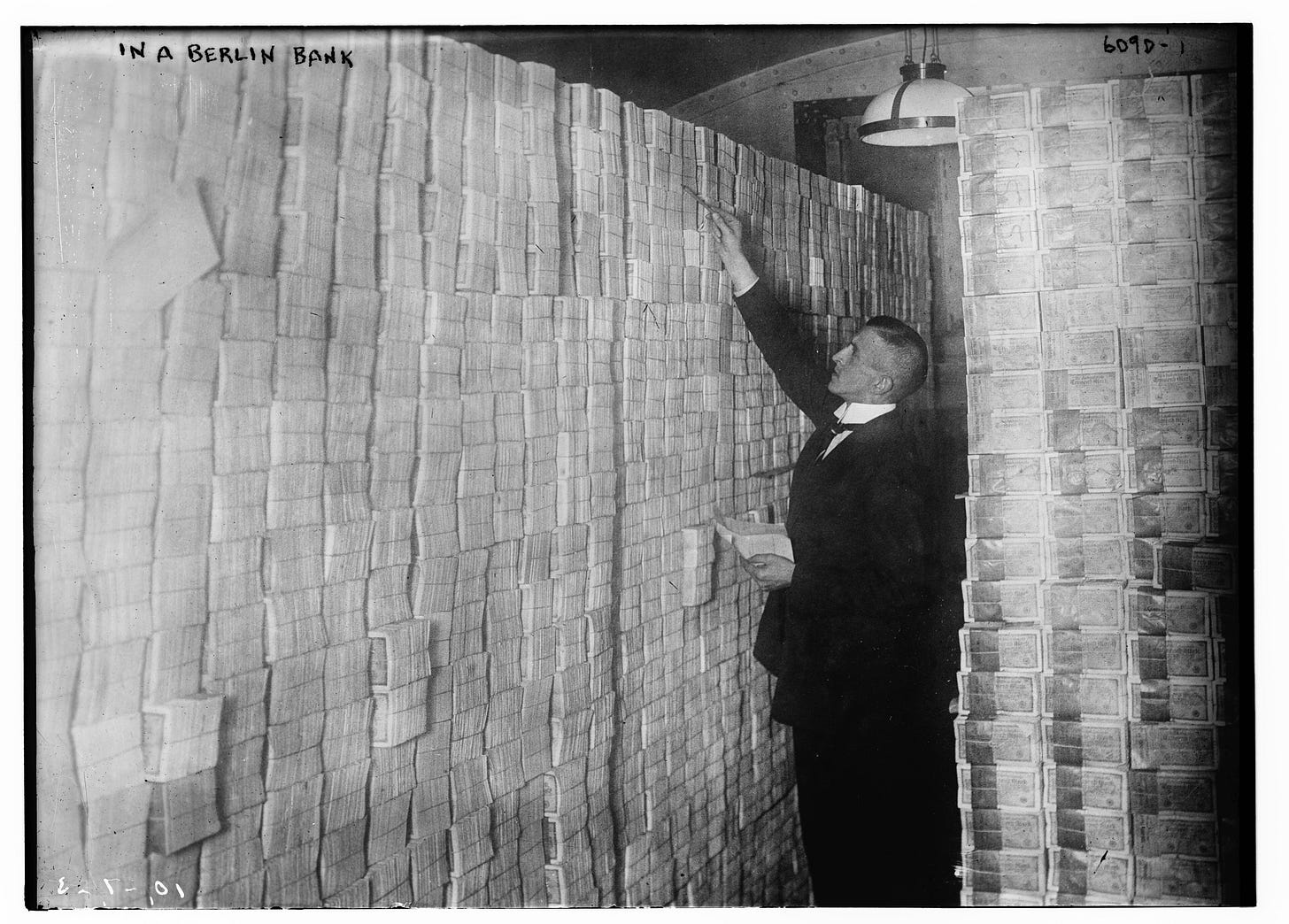

A hundred years ago in Germany, the world saw hyperinflation of the money supply like never before. According to Smithsonian Magazine, “In January 1923, a dollar cost 17,000 marks. In December, the exchange rate topped out at 4.2 trillion marks to the dollar.”

What’s playing out with the Internet today is something like what happened in Weimar. What’s coming is a total devaluation of content. And if this continues to be the dynamic, the perceived value of content, whether good or bad, will drop to zero.

Then what happens is anyone’s guess. Will it be a kind of “flight-to-quality” in which people discount digital, preferring channels that are more trustworthy, channels that can’t be faked.

We may soon find out.

The dead Internet, our prize

I hope that the slop stops. In part, that’s why Un•AI•ify was created, to reveal signals of AI writing instantly, to create greater awareness of the common patterns. So far, it is not making a dent.

Really, how could it? For nearly two decades the world has been trained to believe that winning attention is all that matters. Using AI to chase attention faster and harder is the arms race of a generation.

Without a change in incentives for slop-creating behaviors, structures that reward abuse with attention and money, we can expect to get more of the same.

The normative behavior online is now to expect others to read what one couldn’t take the time to write. Until we see this techno-powered asymmetry for what it is, i.e. a sign of disrespect and a shameful lack of skin in the game, the slop will continue.

If nothing changes, the fringe “dead internet” theory may become law.

Notes

¹ I have experimented with calling attention to the abuse of AI writing by users on 𝕏 and even LinkedIn. I don’t recommend doing this, the result is punishing. If you do, you can expect the original (AI-powered) poster to argue that, “AI is irrelevant. Argue with my ideas!” They will miss the asymmetry at play, which is the gross imbalance in tactics that disadvantage the person who called out the behavior: The heckler gets reverse heckled with the power of the AI. The offender can “outwrite” you by an order of magnitude, instantly. Adding insult to injury, unwitting white knights who are sympathetic to the AI rhetoric of the original poster may even jump to their defense. Alternatively, arguing with their content, i.e. in good faith, invites more AI-written replies, which tend to propagate new arguments.² You lose at every step.

² The most egregious and damning example of how AI propagates ever more arguments comes with the use of “It’s not X. It’s Y.” This refrain always offers two arguments in one. To counter you must take seriously the negation (Argument 1, “It’s not X.”) and the following affirmation (Argument 2, “It’s Y”). Every LLM abuses these refrains so ubiquitously and unavoidably that even when prompted to stop their use, they persist. Arguing with an AI-powered poster is a losing battle.